Part 4: VoIP Business Owner Turned A.T. Thru-Hiker

This is the fourth in a four-part series from Guest Blogger and UpLync CEO Mike Bristol sharing his six-month epic experience running a VoIP phone business as a thru-hiker on the Appalachian Trail.

This is the fourth in a four-part series from Guest Blogger and UpLync CEO Mike Bristol sharing his six-month epic experience running a VoIP phone business as a thru-hiker on the Appalachian Trail.

I hadn’t made it off the return flight from Maine before the barrage of questions started about my Appalachian Trail (A.T.) thru-hike. “You went how far? How long did it take you? What did you eat? Did you see any bears?”

I always enjoy answering these questions and discussing my experiences. But, the questions that nearly always stump me are, “What’s your major takeaway? What did you learn?”

It’s taken a while for the fog to clear from my mind, my sore feet to heal completely, and the painful memories of those last few difficult weeks to fade. Now that almost a year has passed, I’ve settled on a few thoughts that stand out.

Life isn’t perfect. Get over it.

I’m not a perfectionist, but I sometimes struggle when things don’t turn out how I expect them to. When living the better part of six months in the woods, something goes wrong each day. The nearly endless cycle of “gotchas” helped me realize that no amount of planning and forethought can ever create the perfect experience every single time.

There’s no such thing as a perfect thru-hike. Every hiker starts with their own expectations. I witnessed a lot of hikers (including myself) who defined successes, both small and large, on the expectations of others. “I’m doing 16 miles today.” Good for you. Does that mean I will fail if I only do 14? Absolutely not.

Perfection is a perception. We define it for ourselves, and it’s usually rooted in unrealistic beliefs and expectations. By focusing on the facts during specific situations and being fair with ourselves in how we handle them, perfection becomes far less about “everything being just right” and far more about how we react to adversity.

Perspective is everything.

The people I met while hiking the A.T. were probably the most diverse group of humans I’ve ever spent time with. I’m not just speaking of cultural or racial diversity. I’m referring to significant differences in those lesser-discussed traits such as stages of life (not just age), world views, morals, and personal opinions about everything from political stances to the best water filtration systems a thru-hiker should carry.

We’ve developed our unique views and opinions using the lens created by our life experiences. It’s important to keep that in mind as others enter our lives and express themselves in ways that might make us uncomfortable or even offend us. We don’t have to agree with them or adopt their beliefs, but we should strive to be tolerant of them and support their right to have ones different than our own.

Have patience.

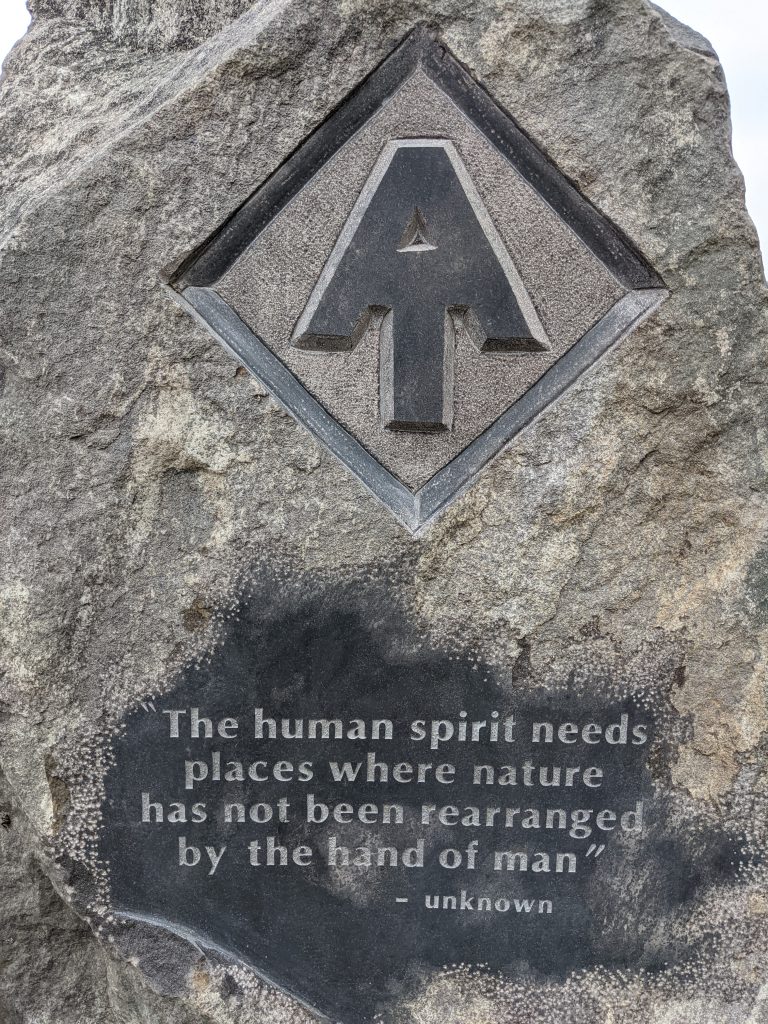

We live in a time of the never-ending quest for immediate gratification. We all want the best in life, and we want it right now. Hiking 2,200 miles is the most amazing way I’ve found to reprogram one’s brain. Virtually nothing in life that’s worth having comes quickly. Almost everything we want that’s meaningful comes with a high cost in time.

Slow down. Enjoy the scenery. Keep the goal on the horizon, but don’t stare at it endlessly. You’ll miss too many of the beautiful experiences along the way.

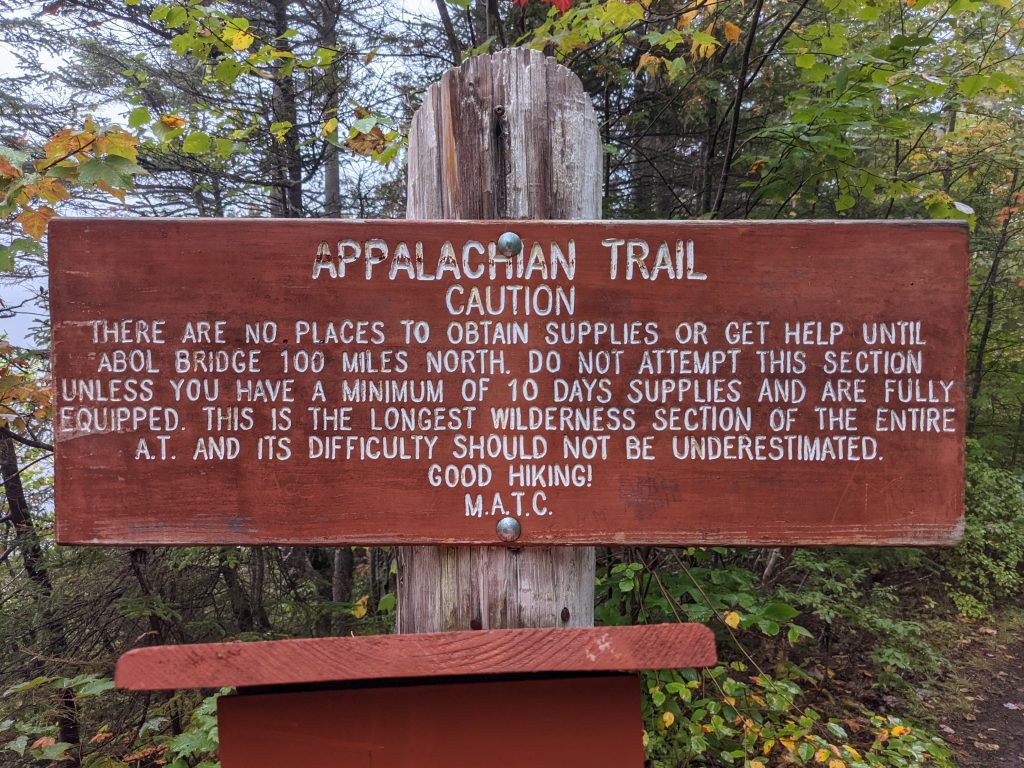

Prepare for the suck.

Prepare for the suck.

I heard a story while on the trail that resonated with me. It goes something like this.

Hiking in cold rain can be dangerous, but we can handle it. Hiking when you’re out of food and your stomach is growling isn’t fun, but we’ll make it through. Hiking when your body aches and you lack rest can be torture, but we do it anyway. Any of these scenarios are commonplace on a thru-hike, and the hiker will endure. However, when any of these things or the other millions of events that present a challenge happen simultaneously with one another, that’s when life gets challenging. That’s when the negative thoughts creep in. That’s when hikers quit.

This is a close approximation of a typical day as a thru-hiker. It correlates with life back in the real world, too. We’re usually fairly adept at handling challenges that life throws at us in our daily lives. But when we get several challenges tossed at us at one time, we start looking for something to hide behind. I found that preparing for and expecting things would go wrong was the best way to deal with them when they eventually did.

A good friend I met on the trail taught me to visualize what it would feel like when and if I realized my worst fears. “So, you’re worried that it will rain and be a miserable day. What specific sensations will you experience if it starts raining? How will those sensations make you feel? Are those expected feelings realistic? What will be the outcome? Will rain stop you from completing today’s miles?” Often when I would analyze my fears from that perspective, it minimized the dread I associated with their slight possibility of coming to fruition. My rational thoughts would frequently quell my fear altogether.

My mindset eventually shifted into what, in retrospect, I refer to as realistic optimism. I remained optimistic about any day’s outcomes while maintaining a realistic expectation that something often would go wrong. Expecting those unpleasant eventualities helped tremendously in dealing with the raw emotions that accompanied them.

That’s All, Folks!

The question I get the most now is – would you do it again? Yes, and I wouldn’t do anything differently except have a better attitude. It took 2,200 miles to teach me realistic optimism. I can only imagine how different my six months in the woods would have been had I embraced that mindset at the start. Maybe I’ll find out someday if I thru-hike the A.T. again. Ready to tag along?